When John Singleton helped cut the trailer for ‘Boyz n the Hood’, he purposely enticed audiences with the majority of the film’s gunplay and violence, hooking potential moviegoers without focusing on the father-son relationship that the film is actually about.

Why? Because “it got motehrf*ckers in the theater,” he said in a RollingStone feature in 1991. “People went with lower expectations,” he continued, “they thought it was the same old bullsh*t action-adventure in the streets of South Central L.A. But when they saw it was more, they really watched it.”

With John Singleton’s passing today, his importance to African American cinema should not be overlooked. His films helped black cinema surmount stereotypical black cinema into black cinema that is three dimensional; films portraying black characters looking outward and inward, with a society that often looks the other way.

To understand why Singleton is important to black cinema and how ‘Boyz n the Hood’ is able to grip the hearts and minds of America to this day requires a brief look at the history of black cinema after the civil rights movement in the late 60s.

“In the late Sixties and early Seventies, everybody was asking questions of themselves and the society around them,” Singleton says in the same interview. “So we had films that were serious and tackled issues, and it was profitable to do that because that was in vogue. Then in the Eighties we were told, ‘Don’t worry, be happy’ by our government, and cinema reflected that. Now, they’re still trying to tell us that, but we know we’ve got a lot of problems. Thought went out of vogue in the Eighties, but I think it’s coming back.”

Born on January 6th, 1968, in Los Angeles, California, Singleton grew up seeing rapid change in America– from its politics to its music, and inevitably to its films. Amongst the ashes of the civil rights movement, black cinema took a spectacular right turn with the emergence of blacksploitation films.

This was a time when black filmmakers were eager to break down the white gates of Hollywood, yelling “black power” into ears that were finally starting to listen. The films that started to come out in the 70s often portrayed hyperviolent and cliche-ridden stereotypes of African Americans but were nonetheless a result of the anger and resentment left over from one of the most important times in African American history.

During all this, Singleton absorbed the fascinating yet dangerous culture milieu that was South Central L.A. It was a region that was at the forefront of The Great Migration, when a relentless flux of African Americans took to urban areas for the promise of the American dream. Instead, however, South Central L.A. became a region plagued by racial inequality, poverty, and violence, all of which Singleton saw traveling between his mother and father’s house in the 70s, leading into the 80s.

With the Reagan administration in the 80s and the Bush administration in the early 90s, both furthering of the “War on Drugs” that mainly focused on the so-called crack epidemic, America shifted in a new direction with star-spangled glasses and moral agency. Unfortunately, this included devasting incarceration rates among low income and minority neighborhoods, with African American men being the main targets of a brutal legal system.

With a new political landscape, black audiences and filmmakers in the 80s looked for something new– films that did not rely on stereotypes that reinforced white prejudices about black culture.

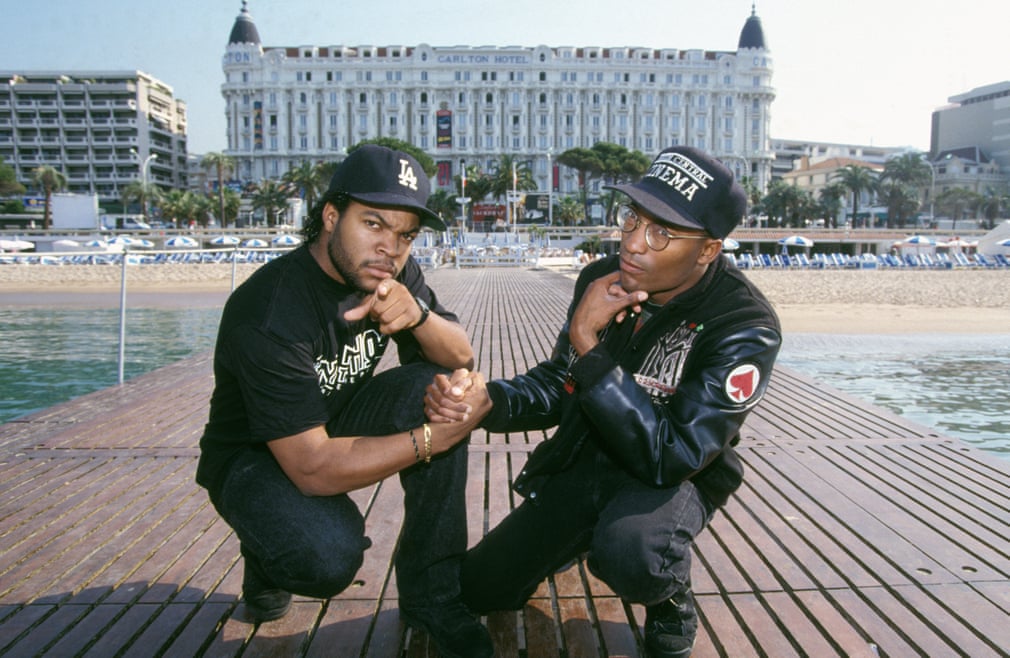

Photograph: United Archives GmbH/Alamy Stock Photo/Alamy Stock Photo

That’s why when John Singleton went to go see Spike Lee’s ‘She’s Gotta Have It’ in 1986, it, “was the turning point in [his] life,” Singleton said. He met Spike Lee at the opening night in L.A. and at that point, he knew he wanted to write films.

With Singleton seeing ‘She’s Gotta Have It’, the idea that black culture could still be told in a compelling way without abiding by cultural stereotypes inspired him, along with an entire generation of filmmakers to do something nobody else has seen before.

“I wasn’t into film to get money,” he said, referring to him enrolling into USC’s film writing program. “I just wanted to make classic films about my people in a way no one had ever done.”

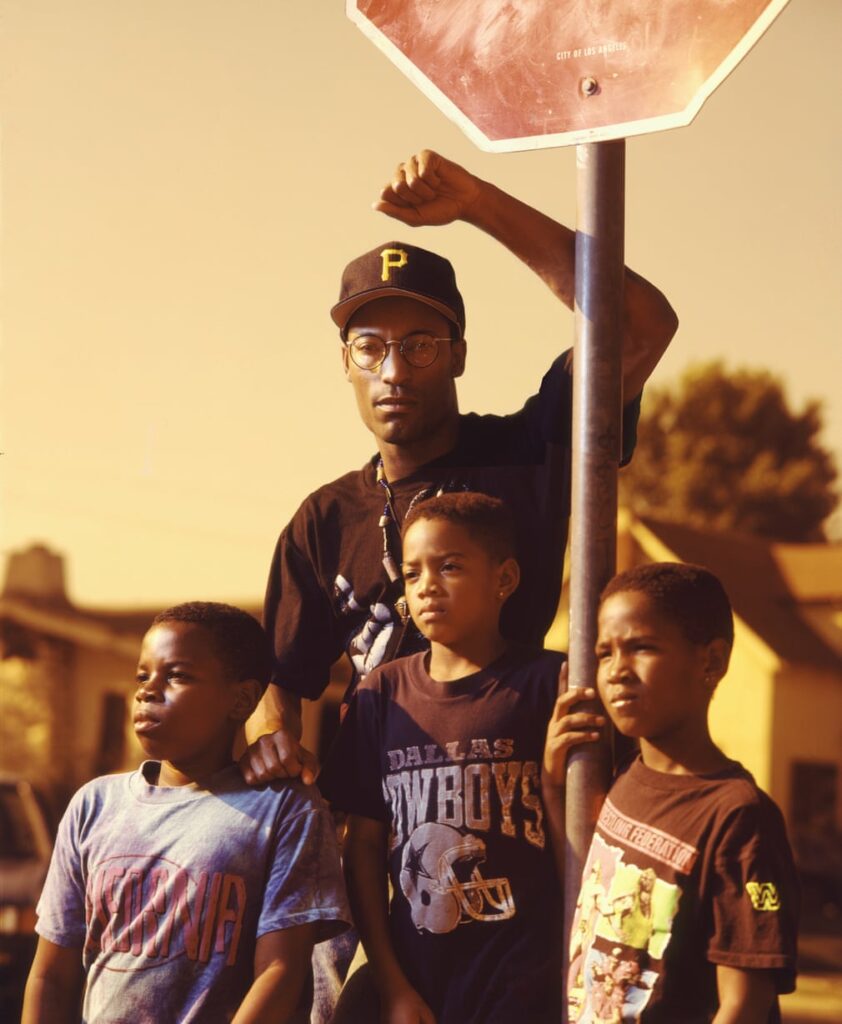

So when Singleton cut the trailer to ‘Boyz n the Hood’, he knew he first had to get audiences in the seats. Once he got past that hurdle, he presented audiences with an unsettling, raw, realistic and unforgettable look at the era Singleton grew up around in South Central L.A. It also offered a complex view of father and son relationships that was indicative of the rapidly changing times the film came out in.

From the film’s opening title sequence with a warning that reads: “One out of every 22 black American males will be murdered each year” to the cultural landmark of having Ice Cube play one of the film’s lead characters, the film cut itself into the history of black cinema by being nominated for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay during the 64th Academy Awards in 1991.

Singleton became the youngest person ever nominated for Best Director (he was 23) and the first African-American to be nominated for the award. Although it didn’t win either award, it proved a film depicting hard truths about African Americans can be commercially successful while not having to pander what white audiences expect.

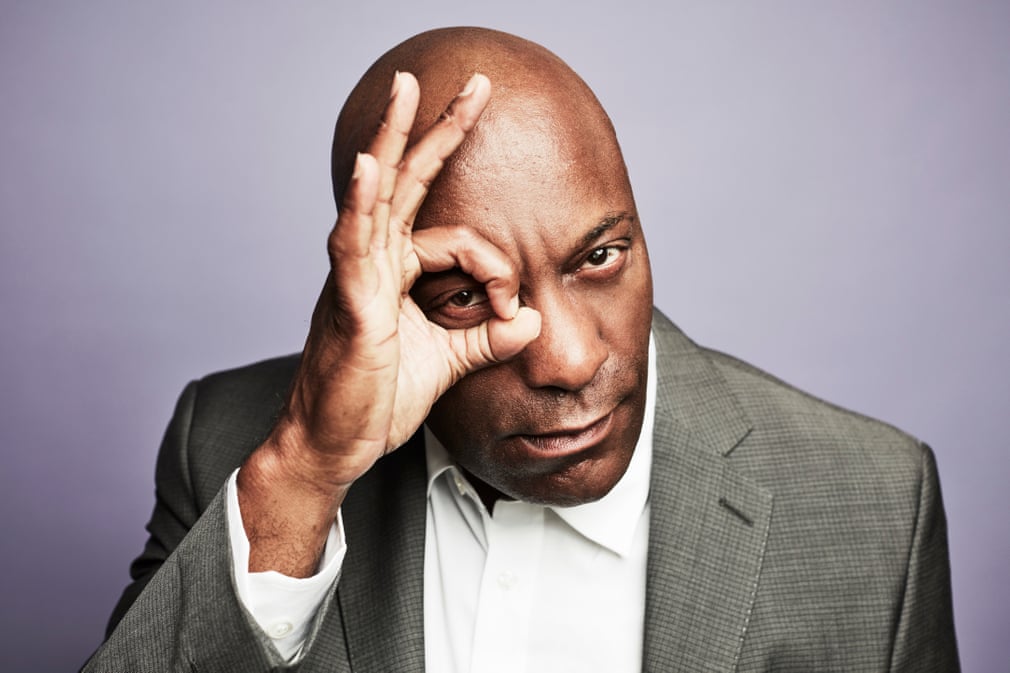

Photograph: Maarten de Boer

Singleton went on to be a successful Hollywood director, making films that depict and consider the implications of inner-city violence, like ‘Poetic Justice’ (1993), and action films like ‘Shaft’ (2000) and ‘2 Fast 2 Furious’ (2003).

He also helped open the door for many other contemporary African American directors that make films that are equally challenging as they are entertaining.

On April 17th, Singleton suffered a stroke and it was reported that he was in a coma. He was then removed from life support on Monday, April 29th and died at the age of 51 at Cedars-Sinai Hospital. The world of cinema will miss him as not only a pioneer of African American cinema but as a quintessentially American artist that pushed boundaries and asked America to finally wake up.

Written by Ryan Nickerson

Feature Image by Pool ARNAL/GARCIA/PICOT/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images